The Big Continent: Asian Cinema Challenge

Week 2: Best Chinese Motion Pictures [Film 2 of 2]

For this week’s installment of The Big Continent: Asian Cinema Challenge, challengers are tasked to select, view, and critique films from the list of Best Chinese Motion Pictures. My review of Fei Mu’s Spring in a Small Town (1948) is already up. This is my second pick from the list, one of my most favorite films of all time, Yi Yi: A One and A Two (2000).

Yi Yi: A One and A Two (dir. Edward Yang, Taiwan, 2000) – ***** – For years since I watched Edward Yang’s Yi Yi: A One and a Two (2000) in my dorm room during my ChemEng undergrad days back in 2009, I hesitated to write about it. I feared spoiling the experience and memory of crying alone at 2 AM, trying to piece together how a three-hour movie could have such an effect on me. At that time, I was not what one might call a professional cinephile. I relied on pirated movies from a DVD shop/bookstore atop Zagu at the UP Shopping Center. Yi Yi was just one of many pirated DVDs I purchased back then. As an undergrad, I was broke, and buying the two-disc film for 100 pesos was a significant expense for me. Now, the challenge lies in gathering my thoughts and articulating why this film practically changed my life.

I. The Child as Philosopher

Two key realizations stand out regarding why Yi Yi made such an impact on me. The first realization occurred in 2009, which I later recognized as my initial philosophical awakening. In Yi Yi, I witnessed the exposition of Nietzsche’s third Zarathustran Metamorphoses – the philosopher as the Child. It took years for me to truly grasp it. In 2009, my understanding of Nietzschean philosophy was rudimentary. It wasn’t until 2014, when I delved into Nietzsche through Deleuze, that the concept of the child-as-philosopher fully materialized for me.

In Yi Yi, the Philosopher-Child is epitomized by Yang-Yang’s character, although the notion permeates several characters and their instances of transformation. According to Nietzsche, the Philosopher-Child represents a crucial step in transcending the asceticism of philosophy. It entails unlearning what we previously knew and embracing a fresh start, akin to a child. Yang-Yang’s character embodies this childlike openness to new beginnings. In the film’s conclusion, he reconciles concepts of life and death, as well as mediation and reality, encapsulating the transformation of the spirit from mere sense-certainty to the realization of the Absolute.

As viewers, Yang-Yang’s character overwhelms us, embodying the intricate process of unlearning adulthood and perceiving the world anew. Edward Yang contrasts Yang-Yang with his ascetic mother, who clings to repetitive faith, while resembling his father, NJ, who seeks new paths in life. Ting-Ting serves as the family’s moral compass, navigating societal ethics through her relationship with her controversial friend Lili and her friends. Together, Yang-Yang and Ting-Ting represent the pendulum between ethics and the theory of knowledge, which forms the philosophical essence of the film.

II. Maoist Theory of Knowledge

We will come to know everything that we did know before. We are not only good at destroying the Old World, we are also good at building the new.

– Mao, “Report to the Second Plenary Session of the Seventh Central Committee of the Communist Party of China” (March 5, 1949), Selected Works, Vol. IV, p. 374.

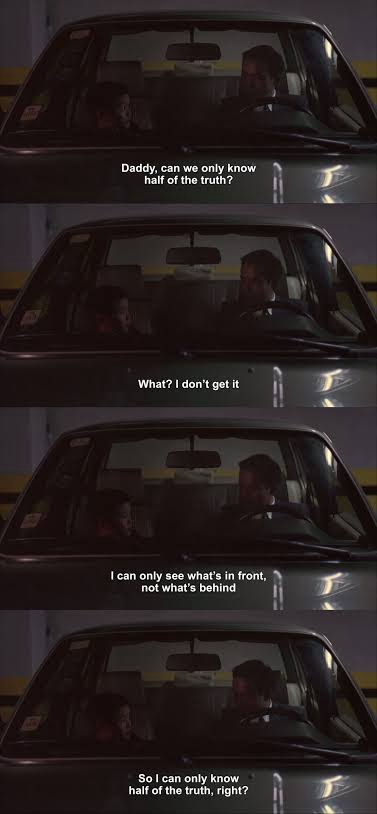

The second realization regarding Yi Yi dawned on me later in my adult life, thanks to Alain Badiou. To me, Yi Yi embodies and explores the problematics of a Maoist Theory of Knowledge, encapsulated in the phrase: “We will come to know everything that we did not know before.” Beyond the Maoist films of the 1960s and 1970s, Yi Yi stands as perhaps the only film I’ve seen with its own theory of knowledge, particularly a Maoist one. Edward Yang cleverly articulates this theory through the Socratic dialogues between Yang-Yang and his father NJ in the car.

Yang-Yang’s insatiable curiosity drives him to seek the whole truth. Yang-Yang conjectures that humans cannot know the whole truth, only half of it. Thus, through his theory of photographic knowledge, he offers access to this other ‘half-truth.’ Yang-Yang’s theory resonates with Maoist ideals of uncovering previously unknown truths. He embarks on investigation and action, with photography serving as his practical solution. It’s a remarkable feat for a film centered on middle-class Taipei.

III. From Yi Yi to the Revolution

Sublation is the crucial step needed to translate the lessons from Yi Yi into revolutionary action. One weakness of the film lies in its idealism. Its portrayal of class dynamics and slow pacing fail to inspire mass action, primarily because its theory of knowledge remains confined within an art-philosophical framework. For philosophical films to incite mass action, they must integrate the mass line into the process of discovering the subjectivity itself through cinema.

Yi Yi marks a significant stride toward philosophical enlightenment. However, it may require another filmmaker to actualize its philosophical theory of knowledge as revolutionary praxis.

###